Did you have any early memories of being interested in the arts?

I was eight years old when I announced that I was a writer, although I had no justification for such a belief! My parents asked me what I wanted for Christmas, and when I asked for a journal and a pen to write in it, they were no doubt delighted, since it was a relatively inexpensive present. Better than a pony, by far!

In terms of first exposure to poetry, I think my key experience was when I read T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” when I was about 12 years old. I just had one of those Emily Dickinson moments where the top of my head blew off as I realised what words could do. I have been a lover of poetry ever since.

Did you start writing poetry after that?

I didn’t actually start writing poetry until I was about 40 years old, I was quite the latecomer. I wrote prose, but didn’t think I had any poetry in me. However, during a particularly intense period in my personal life I felt driven to write a poem, and realised I loved it. I confessed to some poets I knew that I had found my form and they replied, “Commiserations, you’ve been bitten by the poetry bug”. Apparently, it’s a curse! Once bitten, you can’t go back, And that’s certainly been the case for me, as I’ve been reading and writing virtually nothing but poetry since.

If we go back a little, did you get support at home or at school?

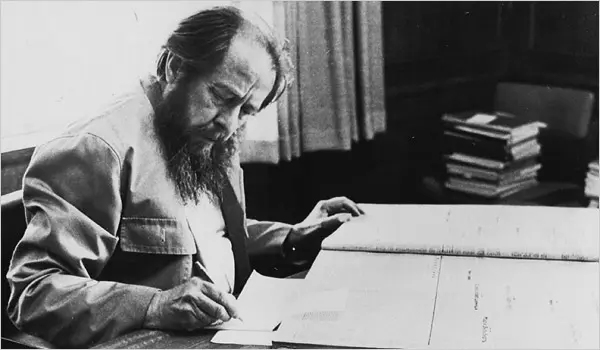

My parents are working class: my dad was a bus driver, and my mum worked in admin. So I didn’t grow up in a house with an academic focus or a vast selection of books. However, my mum did have a job at a local library and that was brilliant because I could go there after school and scour the aisles. Besides devouring fiction, I was particularly drawn to aisle 9, which housed the esoteric, psychological, and philosophical books. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams and Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago were early favourites. I was clearly an odd child!

Eventually, I went to Sydney University to study English Literature and considered an academic career, but I hated the process of deconstructing text. I would be inspired by books which were dynamic, alive, and thrilling, and was dismayed to be asked to pin them down, dissect them like specimens in biology. That just didn’t appeal. It felt like the antithesis of literature.

After finishing my English Lit degree, I enrolled to study Law but quickly dropped out, realising I would never make it in such a dry discipline. Instead, I travelled to India and became a Yoga teacher

—I blame it on the esoteric books from aisle 9 in the library!

Given that you came to poetry a little later in life, how did you develop the craft?

When I first started publishing poetry, people would ask me who my teacher was. I didn’t have one. There were no creative writing programmes at university in those days; you studied Literature, but no one actually ‘taught’ you how to write. Which was probably a blessing. You learnt by osmosis, by reading. Luckily for me, even before coming to poetry, I was a naturally rhythmic writer, so the musicality of the form came easily. Beyond that, I developed my craft through intuition, trial and error, and revision.

Also, when I turned to poetry, my family was going through a difficult time, which I think is quite a common way to discover the form. Basically, when the shit hits the fan, when life is dark and troubled, poetry, as an artform, rises to the fore. It’s the perfect vehicle for those sorts of emotions. There was also a practical element for me I desperately needed to express myself, but I had three small children and didn’t have much time to write. I needed to be able to compose in my head, on the go, in short bursts. So both practically and artistically, poetry was the perfect vehicle for me at the time.

I also believe that if you start writing later in life, as I did, you can experience a quicker progression. You might have done a lot of the unconscious work over those years when you were reading and living but not writing, and when you finally pick up the pen, your voice is ready, matured.

What kind of ideas do you investigate through your work?

I don’t start with ideas or themes; I start with feelings. I start with an emotional impetus. I let that ignite the poem. I think a poem is a living thing, and in order to affect someone else, it must contain an emotional spark that can be passed from one heart and one mind to another; otherwise, the poem is empty, it has no power to move you. I like poems that give you a real punch in the gut, that stick the knife in and give it a good twist. If I don’t have that happening inside me when I write, I don’t see how I can pass that intensity or experience on to the reader.

Having said that, my first drafts are usually shambolic, and I wouldn’t want other people to see them. But when I’m writing a first draft, my aim is to try to capture its igniting emotional spark and hold and grow that into the body of the poem. Then the conscious redrafting begins, where the focus is on editing the poem to make it as strong and as true-to-itself as it can be.

You are the kind of writer who is waiting for inspiration to kick in. Would that be reasonable to say?

Yes. I don’t like to force the process, to push for something to happen, and that can be quite scary. Sometimes it means that you just have to sit with nothing and hope that the work is going on in the background.

Consequently, after finishing each poem, I always fear it may be my last! But thankfully, so far, another one has always popped out.

If you want to know more about the work of Michele Seminara see the following link – micheleseminara.net