What are the key elements you are looking for when you design a production?

I think the key elements are relatively simple. If it is opera or ballet, it’s the music. I let the music guide me. Hopefully, you get to talk to the director or the choreographer, sometimes you don’t. In the big classic ballets like Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty much of the choreography is based on the original Petipa choreography and the director often doesn’t deviate much from these. I do tend to do a lot of research whatever the project.

With La Bayadère I never really got to talk to Asami Maki at all about the production. I did write to her asking her to consider the story from which the ballet comes. It’s from a wonderful Indian epic Play in Seven Acts by Kālidāssa called Abhijnānaśākuntalam (‘The Recognition of Śakuntalā’), but Maki San only wanted to follow the Bolshoi Ballet version. Although, having said that, she did add a wonderful ending and she did give me a file of coloured prints of Indian costumes gathered by her father. He had spent time in India and many of my costume designs were based on the authentic clothes in the photographs.

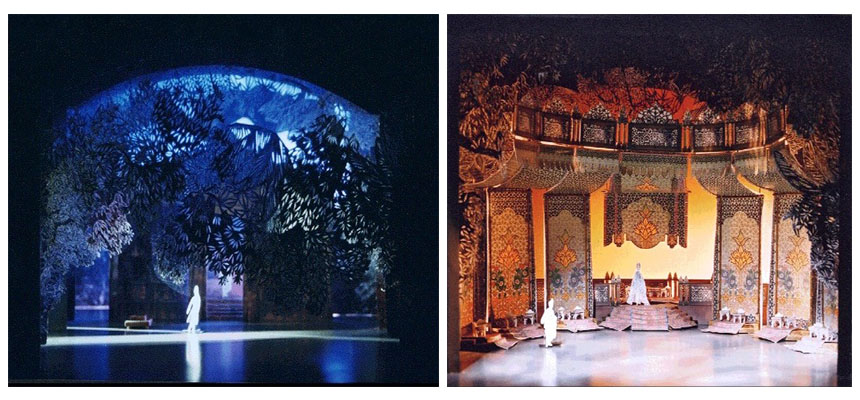

With La Bayadère I designed the sets on computer using a combination of Vector CAD and Photoshop at a scale of 1:50 and although I did make a model the designs were delivered on disc. The costume designs were drawn on A4 paper and of course there were the usual materials to be found and I worked with the Fujikake Company in Tokyo who printed silk with authentic Indian patterns.

Sometimes you miss the boat entirely. Early in my career, I designed ‘Le Spectre de la Rose’ for the Royal Ballet Touring Company. They wanted something which could be brought on and off the stage very quickly, rather than the full interior bedroom box set that was in the Nijinsky original. It is quite a short piece, maybe twenty minutes, and it took just as long to strike the set? This didn’t matter when Nijinsky performed because he took curtain calls and threw rose petals from his costume into the audience for at least that long.

One cold morning, a Saturday morning, the company had assembled on the Sadlers Wells stage because Stanislas Idtzikowski who had been Nijinsky’s understudy and had danced the male role many times was coming to talk about the ballet. Until then I had not been able to talk to anyone about what the ballet was about or why it was such a seminal work. Idtzikowski not only demonstrated the male role but also the young girl’s role. I had made the set in steel with lace curtains, and also the bed and a chair. But as Idtzikowski marked the steps the ballet unfolded in front of me and I knew that everything that I had designed had failed to capture the spirit of the ballet! Nevertheless some of the ballet critics liked what I had done.

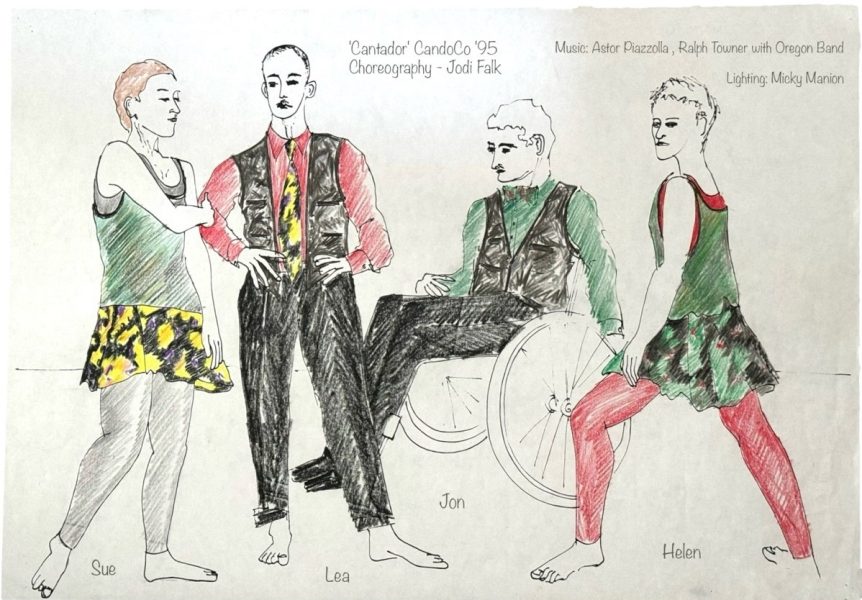

With modern dance works there is much more scope for experimentation. I like to go to rehearsals and talk with the performers and discuss requirements in terms of portability, materials and costs.

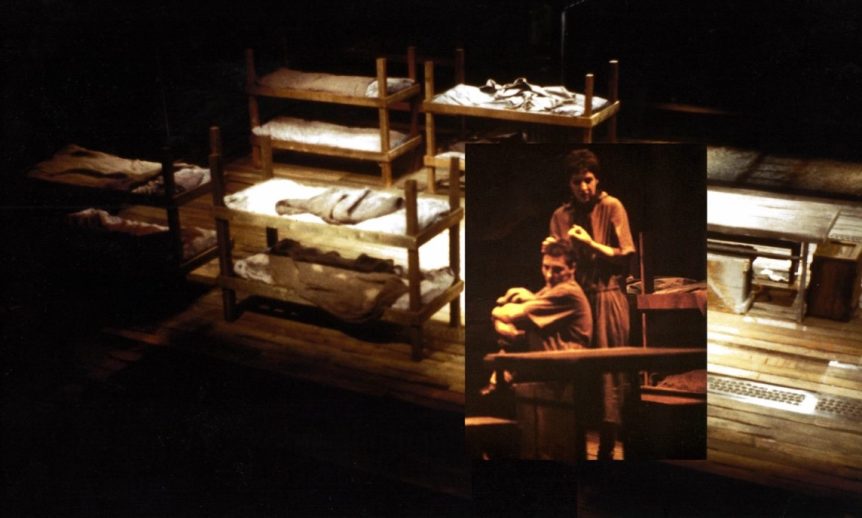

I designed ‘Playing Moliere’ in Adelaide – a play about five women in a labour camp at the end of World War II. I had very simple costumes made for the prisoners. The actors wore them during rehearsals and I would occasionally rip them or take them and drag them through mud and generally destroy them and then they would need to be repaired. I insisted that the actresses repaired them themselves, but only from the material on the set, making a headscarf or something else from the torn material. I like to think this gave the production and the development of their individual characters an authenticity which would not otherwise have been achieved.

I’ve worked several times with Ken Campbell. Ken was another ‘maverick’ . He often said hugely contentious things like why spend time rehearsing actors! “If they are any good they know how to ‘act’… after all if you employ a plumber you don’t ask him to rehearse mending a tap”.

I’ve always believed that talking to as many people as possible involved in the process is never wasted, because bringing a production to the stage is a process, but with people like Ken…. well he just liked you to get on with it and amaze him!

Ken invited me to design an ‘exterior’ set for Camillas’ Gregorian H. P. Lovecraft Opera at the ‘Liverpool School of Language, Dream and Pun’.

He was ‘amazed’…that the whole set fitted into the boot of a car!

As another example, the extraordinary founding director of Can-do-Co, Celeste Dandeker, invited me to design a production for her disabled and non-disabled company, and I felt very privileged to have been asked. ‘Cantador’ was choreographed by Jodi Falk and I spent many wonderful hours in the rehearsal room with her and the dancers. I took lots of photographs, as a collaborative and inclusive work emerged, and designed the costumes based on these.

It seems to me, looking at it from a layperson’s perspective, there is a huge amount of theory, thought, the question of materials, space, to consider. Is that accurate?

Yes, in general terms you’re quite right, but the scale of a production affects these parameters. As I said earlier, all the big classic ballets, for example, have pre-defined choreography, so there is a sense in which in general terms artistic directors know what’s required, ballroom, lake, woods etc. What differs is the interpretation and era in which a production is set.

If we talk about ‘La Bayadère’, the last big ballet I designed, that is at a totally different scale. I was invited to design it by Asama Maki, because I had worked with her own company, Asami Maki Ballet Company some years before remounting ‘Tales of Hoffman’ and that had been a big success, revived several times and they still have the production in storage.

I got on well with Maki San and her staff who had worked on that production and years later I met her and her assistant Yoshiko Nagata in London. I didn’t think anything would come from that meeting but then soon after we had moved from my studio in London to Warrenpoint – long story, don’t ask – I got a phone call from Yoshiko in Tokyo “Livingstone San – very difficult find you, Maki San appointed Artistic Director at National Ballet and want you design new production.”

One phone call and suddenly I found myself designing a ballet with five big sets, something like a hundred elaborate costumes, props and lighting – all from a box room in Co. Down. Life can be very surprising.

Soon I was flying back and forth to New National Theatre Tokyo (NNTT) from Warrenpoint. At the request of the production team at NNTT I designed the sets and lighting using Vector CAD software programme at a scale of 1:50 and I had to learn a whole new way of working – I had worked with computers in Australia before, but this proved to be a steep learning curve. I still had to make scale models to show to Asami Maki and her team and fortuitously I found that I could print all the hanging pieces onto A3 sized card.

I had designed large fabric tent-like hangings for the second Act and I went to the workshop to see how they were to find that they had been printed directly from my designs on computer disc onto fabric. Similarly, Indian fretwork in the palace set was laser cut! These are now standard practice but completely new to me then.

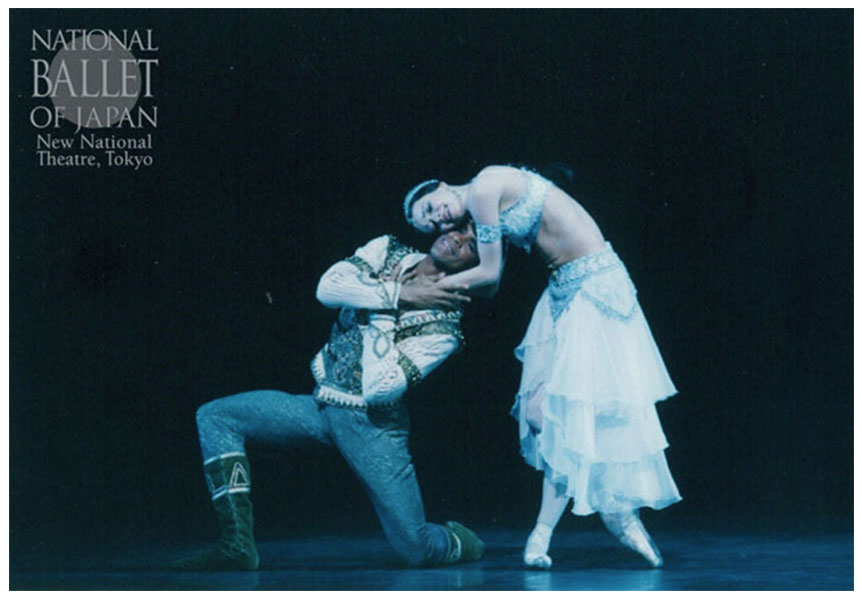

I drew all the costume designs by hand and I worked with Mr Fujikaki whose wonderful firm produced beautiful, printed silk material, for many of the costumes with traditional Indian patterns that I had specified. My drawings were interpreted and made into something wonderful by the talented costume makers. I am always amazed at how scribbles of mine can be turned into the most beautiful headdresses and jewellery and how talented costume makers turn a drawing into costumes that stand up to the rigours of performance and yet move and dance on the stage. I’m trying to make it clear what a huge collaborative process a production of this scale is.

One problem was finding an assistant locally to work with me. I finally found a very talented and patient young lady who had recently graduated from Art School but lived in Belfast. She was happy to commute in order to get the experience and she helped me enormously in pulling the models together.

Do you feel this work was successful?

How can I answer that?

La Bayadère is still in the repertory of the National Ballet of Japan and was on again at the NNTT in April this year (2024). A recent review said, “production had all the formal beauty of classical ballet, with spectacular, rapid stage transformations and lush stage art with deep oriental shades. These qualities gave the production an originality not seen in the original version, and made it a great success.”

Jack Lanchberry, who arranged the Minkus score for this production of La Bayadère, was very complimentary about my designs. He wrote to me after the first night saying that he was very happy to have something worth looking at while he was in the pit and happy to see the colours of his music score reflected on stage.

The experience of designing is itself a process and there are many parts and elements which go into what eventually become the final designs. For me there are always improvements that can be made (and sometimes should be) and that is part of my process too. I guess that is true for most, if not all creative artists. Perhaps it is the search for something ’other’ that impels us to go on and that is as true with La Bayadère as any of my other projects. Is it the one I’m proudest of? Probably not.

To see more of Alistair Livingstone’s work go to the following links: