What kind of issues regarding Palestinian life did you want to discuss through your work as a dancer?

I come from a deeply political family. My grandfather was shot by the occupiers while he was working as a nurse, helping someone who was injured. My father spent four years in prison, one of my uncles seven years, and another uncle lived in hiding for sixteen years.

Growing up in these circumstances was extremely difficult. My father had very limited work opportunities because of his status as a former political prisoner, so I didn’t see him often. That environment made it hard for me to express my emotions. But the moment I started dancing, something changed I found a platform where I could scream without screaming, if that makes sense.

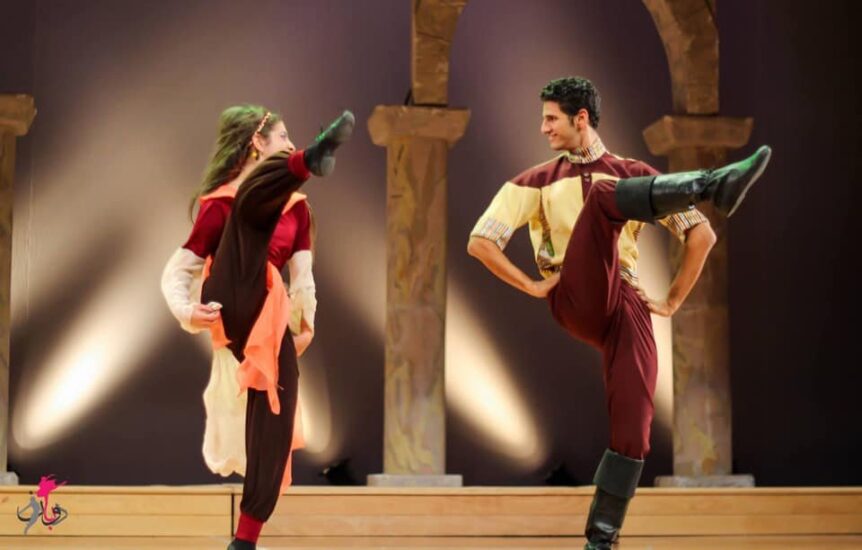

Through dance, I was finally able to express myself my life as a Palestinian, my identity, my emotions fully and without restriction.

You talk about Folklore. Could you say a little about that?

For a long time, I never really understood why Folklore mattered. I kept wondering: What’s the meaning behind each movement? Why this particular hand gesture? Why do we dance with this kind of energy? When I began my Master’s degree, these questions became urgent. My professor challenged me: “Why do you do these movements? What do they mean?” And I realized I didn’t know. So, I started researching. I wanted to understand our traditions, to know what makes up my identity as a Palestinian. I began learning about my grandfather, about our ancestors. Why they lived where they did, how they worked, how they survived, and how our culture developed. I focused on Palestinian tangible and intangible folklore, especially dance, because it had never really been studied in depth.

I discovered that many Dabke movements reflect ancient agricultural rituals. Others reflect our resistance to occupation. Palestinian life—our joys, our struggles, our resilience is mirrored in these movements. I began to see Folklore not as something stiff or frozen in time, but as a living mirror.

You researched your cultural history?

Yes. And I realized that many Palestinians today don’t view Folklore the way I do. Because our land, our identity, and so much of our heritage have been stolen, people feel the need to protect Folklore as something fixed, something untouchable. I understand that impulse. But to me, it’s a misunderstanding.

Heritage is fixed it’s preserved. But Folklore is both fixed and dynamic. Heritage is part of Folklore, but Folklore is not just heritage. You can’t lock it away. I want to challenge this stereotype of Folklore as unchanging.

I’ve dedicated my studies and my work to developing this understanding. Coming from East Jerusalem, where opportunities to learn about our own history and culture are restricted, I’ve felt personally suffocated. And I see that many young people today aren’t being taught Palestinian history at all.

Folklore can change that. It can connect young people to their ancestors, to their roots, to what it really means to be Palestinian. It can teach them their history in a way that’s alive and embodied not just written in books.

I believe Folklore is essential for shaping our identity and resisting the occupation. It has many layers and many reasons behind it. And it must remain alive rooted in our traditions but open to growth so that it can connect past, present, and future generations.

If you would like to see more of Hanna Tams’ work go to the links below